Separating Conflict from Combat: Part 1

No matter how much we dislike it, the potential for conflict is everywhere. Whether it’s something as simple as a scheduling conflict or as explicit as a conflict of interests and priorities when writing budgets, the most fundamental rule is to address them in a way that keeps the conflict from turning into combat.

Ironically, it is often through the efforts and extents people go through in attempt to avoid the subject of the conflict that they end up making a bad situation worse, as problems are allowed to fester.

I once worked with an executive team who were all painfully conflict averse. Rather than confront a colleague who everyone knew was going to miss a critical deadline, they would wait until the deadline was officially missed and then end up screaming at each other… which was exactly the combat that they were trying to avoid in the first place.

Why does this combat happen, and how can you avoid it while still solving the problem?

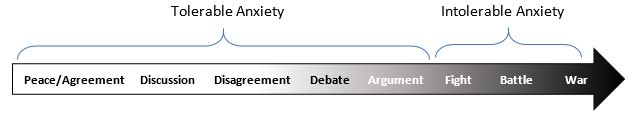

Conflict can be viewed on a scale of progressive intensity, with Peace and War as being opposite extremes, which might look something like this:

Understanding that each increasing level of conflict brings in equally increasing level of anxiety, the key question then becomes: For you personally, at what point along the scale does the anxiety become intolerable?

If you are someone with a low tolerance for conflict-anxiety, you may view the scale like this:

From this perspective, you can only have a conversation comfortably as long as you know that you will not have to discuss anything that will make either or both people unhappy, because unhappiness reflects conflict, and conflict triggers anxiety, which is not tolerable at almost any level. This is why people who are highly conflict-averse may tend to avoid engaging in some important conversations.

On the other hand, if you have a high tolerance for anxiety, you might not perceive the anxiety until the intensity of the conflict has increased markedly. You may view the scale more like this:

To people like you, a good intellectual debate is just that: a debate, to explore the differences in ideas, whether for the purposes of trying to learn from each other, or to persuade the other person to change their view. As long as the discourse doesn’t get personal, most commentary is fair game, within reason. Unfortunately, what’s fun and interesting conversation for you feels like combat to others, and makes them want to leave the room.

Can you imagine if these two types of people were working on the same team? It would be like a perpetual game of cat-and-mouse, with one person constantly running away to avoid uncomfortable conversations, and the person obliviously and futilely chasing her (live or virtually) in order to force those very conversations, again and again.

Ultimately, any kind of conflict can be discussed productively and successfully without evolving into combat. But the crucial first step is awareness of your own orientation on the conflict scale above, followed by careful consideration of where the other person falls on that same scale.

Once you stop asking yourself “why that person is always picking a fight with me,” and start to realize that he doesn’t recognize his conversations as being combative at all, your response to him and his comments can be very different, particularly because you can depersonalize them and realize it’s not a personal attack.

From there, think about where you and she need this issue to occur on the scale in order for both people to feel safe discussing it. Then and only then can you adjust your communication style effectively to mitigate the risk of anxiety and the perception of combat when having potentially difficult conversations with people.

That’s what we’ll look at in Part 2.

Look for Part 2 of Dr. Laura Sicola’s column next week!